Rule Sanity Checks

The rule_sanity option enables some automatic checks that can warn users about certain classes of mistakes in specifications.

There are several kinds of sanity checks:

Vacuity checks determines whether rules pass vacuously because they rule out all models.

Trivial invariant checks detects invariants that hold in all states, rather than just reachable states.

Assert tautology checks determines whether individual

assertstatements are tautologies.Assertion structure checks detects unnecessarily complex

assertstatements.Redundant require checks detects unnecessary

requirestatements.

The rule_sanity option may get one of the none, basic, or

advanced values to control which sanity checks should be executed:

When not using the

rule_sanityoption at all, or when using it with the valuebasic, the vacuity and trivial invariant checks are performed.When using the value

none, no sanity checks are performed.When using the value

advanced, all sanity checks will be performed for all invariants and rules.

Each option adds new child nodes to every rule in the specification. If any of the sanity check nodes fails, that node will be marked with a red icon, and so will the parent rule’s node:

If a sanity node is halted, then the parent rule will also have the status halted.

The remainder of this document describes these checks in detail.

Vacuity checks

The vacuity sanity check ensures that even when ignoring all the

user-provided assertions, the end of the rule is reachable. This check ensures

that that the combination of require statements does not rule out all

possible counterexamples. Rules that rule out all possible counterexamples

are called vacuous rules. Since they don’t actually check any

assertions, they are almost certainly incorrect.

For example, the following rule would be flagged by the vacuity check:

rule vacuous {

uint x;

require x > 2;

require x < 1;

assert f(x) == 2, "f must return 2";

}

Since there are no models satisfying both x > 2 and x < 1, this rule

will always pass, regardless of the behavior of the contract. This is an

example of a vacuous rule — one that passes only because the

preconditions are contradictory.

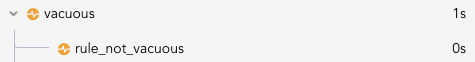

A vacuity check adds a node called rule_not_vacuous to each rule. For example, the rule report for the above vacuous rule will look like this:

The vacuity check also flags situations where counterexamples are ruled

out for reasons other than require statements. A common example comes from

reusing env variables. Consider the following poorly-written rule:

env e; uint amount; address recipient;

require balanceOf(recipient) == 0;

require amount > 0;

deposit(e, amount);

transfer(e, recipient, amount);

assert balanceOf(recipient) > 0,

"depositing and then transferring makes recipient's balance positive";

Although it looks like this rule is reasonable, it may actually be vacuous.

The problem is that the environment e is reused, and in particular

e.msg.value is the same in the calls to deposit and transfer. Since

transfer is not payable, it will always revert if e.msg.value != 0. On the

other hand, deposit always reverts when e.msg.value == 0. Therefore every

example will either cause deposit or transfer to revert, so there are no

models that reach the assert statement.

Trivial invariant checks

The Trivial invariant sanity check ensures that invariants are not trivial. A trivial invariant is one that holds in all possible states, not just in reachable states.

For example, the following invariant is trivial:

invariant squaresNonNeg(int x)

x * x >= 0;

While it does hold in every reachable state, it also holds in every non-reachable state. Therefore it could be more efficiently checked as a rule:

rule squaresNonNeg(int x) {

assert x * x >= 0;

}

The rule version is more efficient because it can do a single check in an arbitrary state rather than separately checking states after arbitrary method invocations.

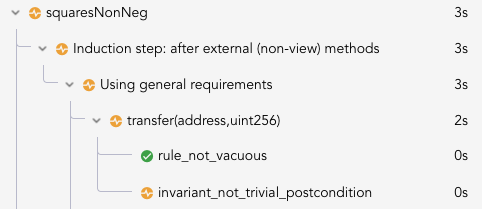

The trivial invariant check will add a node to each method under the induction step of invariants named invariant_not_trivial_postcondition. For example, the rule report for the above squaresNonNeg invariant will look like this:

Assert tautology checks

The assert tautology sanity check ensures that individual assert statements

are not tautologies. A tautology is a statement that is

true on all examples, even if all the require and if conditions are

removed. Tautology checks also consider the bodies of the contract functions. For

example, assert square(x) >= 0; is a tautology if square is a contract

function that squares its input.

For example, the following rule would be flagged by the assert tautology check:

rule tautology {

uint x; uint y;

require x != y;

...

assert x < 2 || x >= 2,

"x must be smaller than 2 or greater than or equal to 2";

}

Since every uint satisfies the assertion, the assertion is tautological, which

may indicate an error in the specification.

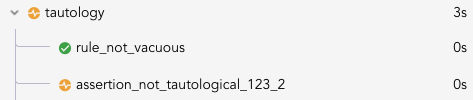

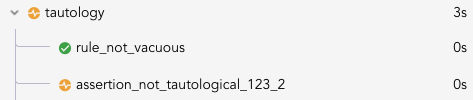

The tautology check will add a node per assert or satisfy statement to each rule. The nodes are named with the prefix assert_not_tautological_<LINE>_<COL>. For example, the rule report for the above tautology rule will look like this:

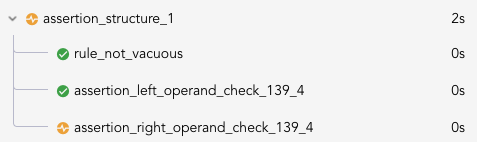

Assertion structure checks

The assertion structure sanity check ensures that complex assert statements can’t be replaced with simpler ones.

If an assertion expression is more complex than necessary, it can pass for misleading reasons. For example, consider the following assertion:

uint x;

assert (x < 5) => (x >= 0);

In this case, the assertion is true, but only because x is a uint and is

therefore always non-negative. The fact that x >= 0 has nothing to do with

the fact that x < 5. Therefore this complex assertion could be replaced with

the more informative assertion assert x >= 0;.

Similarly, if the premise of the assertion is always false, then the implication is vacuously true. For example:

uint x;

assert (x < 0) => (x >= 5);

This assertion will pass, but only because the unsigned integer x is never

negative. This may mislead the user into thinking that they have checked that

x >= 5 in some interesting situation, when in fact they have not. The simpler

assertion assert x >= 0; more clearly describes what is going on.

Overly complex assertions like this may indicate a mistake in the rule. In this

case, for example, the fact that the user was checking that x >= 0 may

indicate that they should have declared x as an int instead of a uint.

The assertion structure check tries to prove some complex logical statements by breaking them into simpler parts. The following situations are reported by the assertion structure check:

assert p => q;is reported as a sanity violation if whenever the assertion is reached:

pis always false. In this case,qis never checked. A simpler way to write this assertion isassert !p;. The node namedassertion_left_operand_check_<LINE>_<COL>will have a yellow icon.

pis always true. A simpler way to write this assertion isassert q;. The node namedassertion_left_operand_check_<LINE>_<COL>will have a yellow icon.

qis always true. A simpler way to write this assertion isassert p;. The node namedassertion_right_operand_check_<LINE>_<COL>.

assert p <=> q;is reported as a sanity violation if whenever the assertion is reached:

pandqare both always true. A simpler way to write this assertion isassert p; assert q;. The node namedassertion_iff_not_both_true_<LINE>_<COL>will have a yellow icon.

pandqare both always false. A simpler way to write this assertion isassert !p; assert !q;. The node namedassertion_iff_not_both_false_<LINE>_<COL>will have a yellow icon.

assert p || q;is reported as a sanity violation if whenever the assertion is reached:

pis always true. A simpler way to write this assertion isassert q;. The node namedassertion_left_operand_check_<LINE>_<COL>will have a yellow icon.

qis always true. A simpler way to write this assertion isassert p;. The node namedassertion_right_operand_check_<LINE>_<COL>will have a yellow icon.

Redundant require checks

The require redundancy sanity check highlights redundant require statements.

A require is considered to be redundant if it does not rule out any models

that haven’t been ruled out by previous requires.

For example, the require-redundancy check would flag the following rule:

rule require_redundant {

uint x;

require x > 3;

require x > 2;

assert f(x) == 2, "f must return 2";

}

In this example, the second requirement is redundant, since any x greater

than 3 will also be greater than 2.

The redundant require check will add a node per require statement to each rule. The nodes are named with the prefix require_not_redundant_<LINE>_<COL>.

![]()

Redundant require is an exhaustive check and will only be executed if neither of the checks for Trivial invariant checks and Assert tautology checks fail.